Sedgwick was killed at the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse on May 9, 1864. Seeking to encourage his men as he chastised them for ducking from the bullets of Confederate sharpshooters, Sedgwick declared “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” Moments later, a Confederate bullet struck Sedgwick in the face, killing him instantly. He was the highest ranking Union officer to be killed during the war.

|

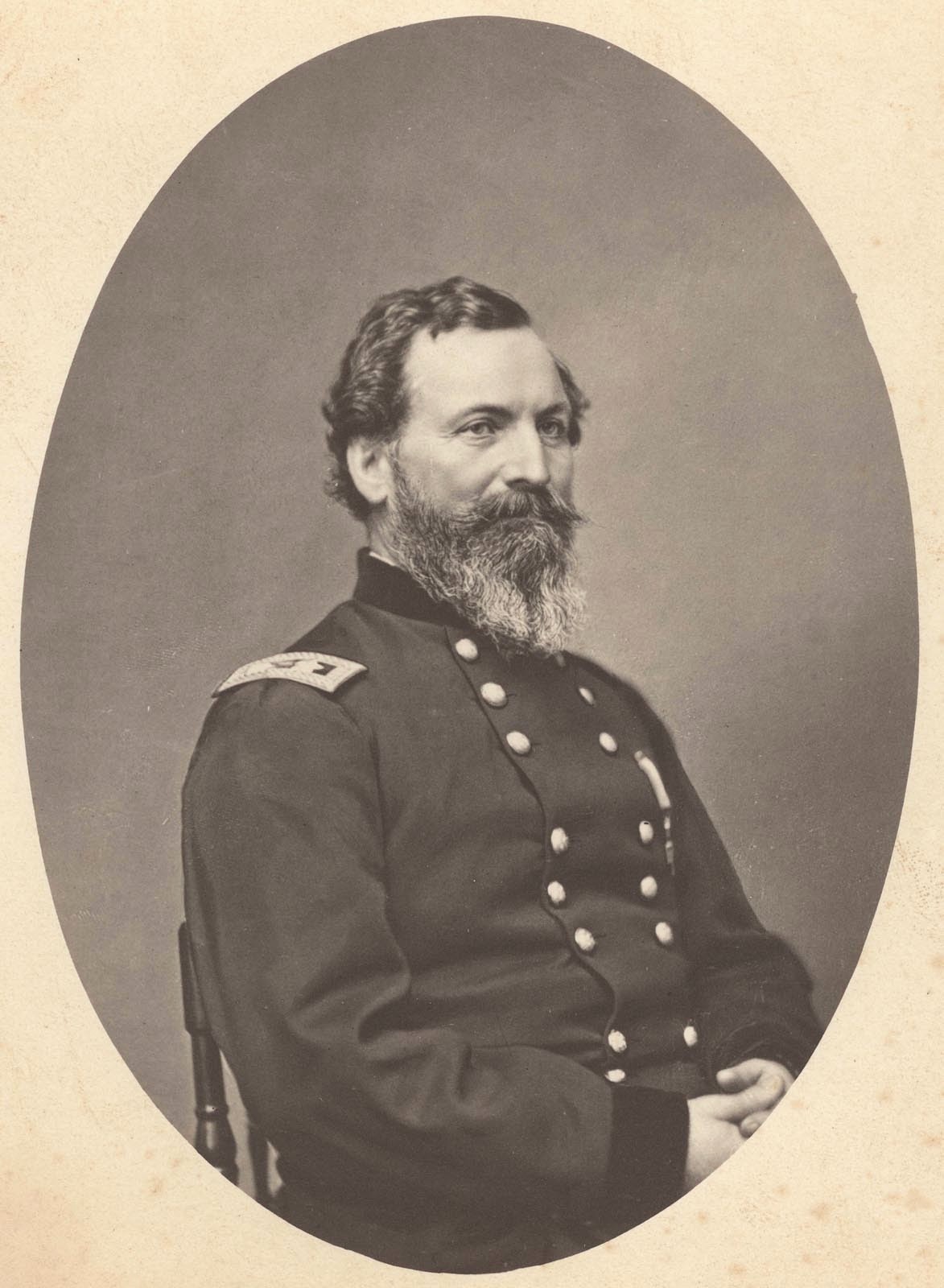

| Civil War portrait of Major General Sedgwick. |

Major General John Sedgwick was buried at Cornwall Hollow on May 15, 1864. Newspaper accounts estimated that about 3,000 people attended (the entire town’s population was less than 2,000). The family rejected the Connecticut General Assembly’s plan to have his remains lie in state in the Capitol at Hartford, and instead held a simple, modest ceremony at Cornwall Hollow.

On the Sunday after he fell, borne by his neighbours, amid the tears of silent thousands, and wrapped in the flag, he was buried in Cornwall Hollow. No military salute was fired above his grave, but one solitary peal of distant thunder sublimely suggested the soldier’s life and death. Sedgwick died, but the victory was won.

~ George William Curtis, Oration delivered at the dedication of the statue to Major-General John Sedgwick, at West Point, October 21, 1868

On Memorial Day in 1892, veterans gathered at Sedgwick’s grave for a special commemoration. An estimated 2,000 people attended the service, which began with a parade to the Cornwall Hollow Cemetery from West Cornwall. Next, members of the VI Corps decorated Sedgwick’s grave, adding their emblem to his obelisk. The other soldiers’ graves in the cemetery were decorated next, followed by a luncheon under a massive tent, and afternoon speeches about Sedgwick.

|

| Graveside service for Sedgwick, Cornwall Hollow Cemetery, 1892. |

Sedgwick’s death was so deeply felt that the officers and men who knew him continued to gather for commemorations for more than half a century. The first statue of Sedgwick was erected at his alma mater, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, in 1868.

|

| Sedgwick state at West Point in 2014. |

A monument to Sedgwick's memory was placed at Spotsylvania Courthouse by the members of the VI Corps in 1887.

|

| Sedgwick Memorial erected by the VI Army Corps at Spotsylvania Courthouse, VA. |

The Sedgwick Memorial at Cornwall Hollow was dedicated on May 30, 1900. The ceremony was attended by an estimated 3,000 people. Cornwall’s residents helped pay for the monument, which was also funded by subscription from people throughout Connecticut. The monument includes a howitzer used by his command during the Mexican War.

|

| Sedgwick Memorial, Route 43, Cornwall, CT. |

An equestrian statue of Sedgwick was erected by the State of Connecticut at Gettysburg in 1913. The horse was modeled after a photograph of “Handsome Joe,” Sedgwick’s horse, and the sword was a copy of the one he wore into battle (now in the collection of The Connecticut Historical Society).

|

| Sedgwick equestrian statue at Gettysburg. |

Most recently, in 1929, a statue of Sedgwick was added to the Capitol building in Hartford.

|

| Sedgwick statue on the Capitol building at Hartford, CT. |